If you take a peek at Tanya Ragir’s Facebook page, you feel as if you’re stepping into the intimate world of a remarkable artist that rarely gets seen. From the images of a softly formed clay female torso in progress, to details of an outstretched hand that resembles a forlorn tree branch, Ragir’s sculptures radiate raw, natural, and thought-provoking beauty.

Having been a highly commissioned and nationally and internationally recognized sculptor during most of her professional life, Ragir’s perseverance and talent have enabled her to pursue her artistic passion on her own terms.

But her career didn’t start out that way. After graduating from UC Santa Cruz in 1976, she moved back to her hometown of Los Angeles and had to confront rejection, gender bias, and not knowing the “right” people who could help her move forward in such a competitive, insular city.

“What we know now in terms of connectivity and networking is so important, but back then there was absolutely no consciousness of that, there was no alumni networking,” said Ragir. “And I just assumed that I would keep going in my art career.”

Ragir had an idyllic childhood in West Los Angeles where she grew up in an artistic family. Her mother was a concert pianist, her father was a noted industrial designer and mechanical engineer, and her aunts played the violin and painted. Her brother, Frank Wolf, is one of the top sound and score mixers/sound engineers in Hollywood with nominations for Grammy and Emmy awards.

“My brother and I would lie under the piano and listen to Mozart when we were children,” she remembered. “He built a harpsichord when he was 15 years old and was the first at UCLA to be a combined musical and engineering graduate. My mom was also an activist and took us to peace marches…it was good place to grow up.”

As an Art and Dance major at UC Santa Cruz, Ragir developed her enthusiasm for sculpting after studying with teachers who inspired her, especially visionary arts educator Professor Gurdon Woods, who helped to design and create UC Santa Cruz’s initial, and very innovative, arts curriculum in the mid 1960s.

“Gurdon Woods’ class was the best class I’ve ever taken – even to this day!” said Ragir. “He had this one class in particular that was outstanding. It consisted of contemporary art history and we went throughout the Bay Area visiting working artists. We would then all look at each other’s work and present someone else’s pieces to the class. The community of artists who were at UCSC at that time was exceedingly strong.”

When she was only 18, Ragir started pouring bronze with sculptor Professor Doyle Foreman, who founded UC Santa Cruz’s foundry program, and taking classes with sculptors and art professors Fred Hunnicutt and Jack Zajac. “The teachers were amazing,” said Ragir. “The Art Department at that time was stellar. It was incredibly, incredibly vibrant.”

One of Ragir’s classmates, Kenny Farrell, just happened to construct the infamous Porter “squiggle” which is actually named “Untitled” and was created in 1974.

Ragir entered UC Santa Cruz when she was merely 16 years old, taking extension classes at UCLA after graduating early from high school, before coming up to Santa Cruz. During her youth, she was also an avid dancer, studying modern dance, ballet, and jazz, and immersed herself in visual art and dance while at UCSC. “One summer I would work in the sculpture department, and then another summer I would take the summer dance program. For me, both were completely integrated because dance continues to inform my work.”

As Ragir developed her art, while still a student, she started showing her work at galleries in downtown Santa Cruz and became locally recognized. “I had my senior thesis show at the Cooper House Gallery near where the Catalyst used to be years before the [1989] earthquake. I did well in Santa Cruz so I was surprised when I came back to LA and didn’t have that same kind of community experience.”

Looking back on that time, Ragir said she lacked any understanding of how to migrate her art practice into an art-related career, and had the difficult task of trying to figure that out on her own. All she knew was how to sculpt so she decided to find work where she could do that while still being able to pursue her art.

“I started working for a ceramicist, so I learned a little bit about clay, and then I started sculpting a kids’ line of mannequins. I really learned that business and then at a certain point, opened my own mannequin business with a partner while I was in my 20s. I became one of the top mannequin sculptors in the country.”

Ragir would sculpt original clay mannequins of live models and then those pieces would be recreated and sold to merchandisers for their stores. “When you make up the human form,” said Ragir in the blog mannequinmadness.com, “they look just that: made up. With a live model the anatomy is authentic. There’s a sense of movement, a feeling that someone is really there.”

After building her business into a major success, she decided that it was the right time to become an independent contractor and work for other mannequin companies as a freelance sculptor. In between those assignments, she had enough time to engage in her own work and considered herself to be her own patron.

Sculpting mannequins also helped to improve her craft and her sculpture kept evolving as she developed her own pieces. Even with her professional accomplishments, she still was asking herself an important question. “I realized that this was my craft, but what was my art?”

About ten years ago, Ragir determined that she wanted to devote her time solely to her personal sculpting projects and to teaching. “I’ve always had another income stream besides only selling my work and doing commissions,” she said, “so that I can feel pure about my art making.”

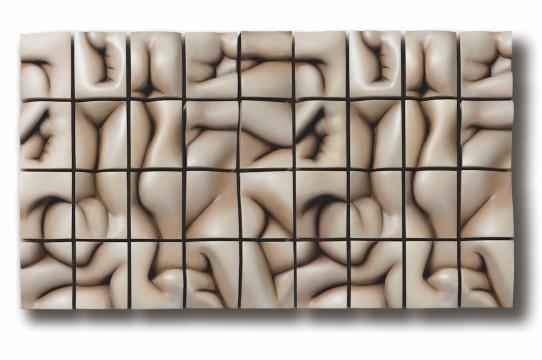

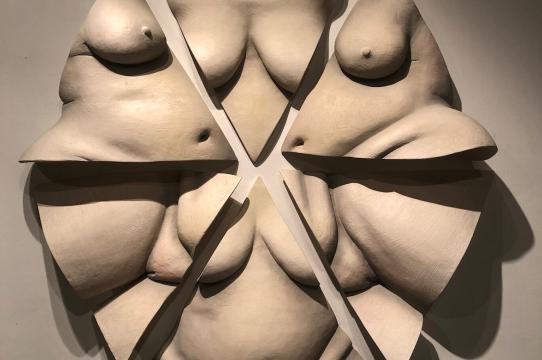

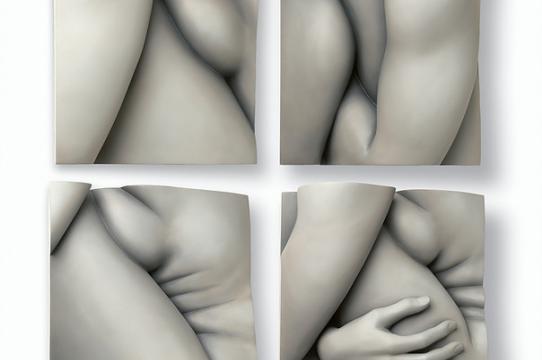

She’s focusing more on ceramics now and is famous for pieces that center on the female form. Using a variety of mediums and styles, her work takes its inspiration from the sensual relationship between land form and human form. Many of her pieces are sculpted in clay and then fired or cast in bronze, aluminum, stainless steel, and resin, and can be found in many private collections.

Of her work, she’s introspective about why she is so drawn to sculpting females in particular. “My relationship to the world as a woman is through my lens, through my experience, through my body….I can sculpt anything, but I think a woman’s gaze on a woman is different than a male gaze. When I work with a woman it’s a collaborative process. I’m a deeply emotional person, so I need to realize how that feels to me and to you, the person I’m sculpting.”

Much of her work also references the integration of power, vulnerability, and creativity as something she understands experientially. “When you get into the ideas of the ‘feminine’, it is beautiful, it is angry, it is a source of creativity. Are we dealing with destruction or integration in the land?”

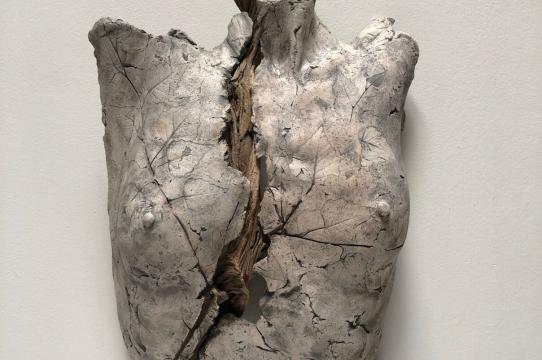

Currently, she’s working on a new series called Hard Wisdom which has her reflecting, as she ages, on her experiences of birth, loss, and death and how that has led her to move away from permanence in her materials. She’s chosen materials for this work that include broken concrete as a form of wreckage from the past, as well as broken clay, leaves, birch, sycamore, and wood found in areas of Los Angeles that were in the recent fires.

She also immensely enjoys her life as a mother of two grown children and being with her longtime partner, musician David Anderson, who is one of the top piano technicians in southern California with many renowned clients.

Ragir is always grateful that she was able to follow her heart and wants to advise students to do the same, but with some forethought.

“It’s not easy. It’s really hard to juggle it all and it’s really important to do the best of your ability, to have community. I would really recommend that students stay in touch with people – community is really important. I’m doing that now. Having an open studio at UCSC with Gurdon Woods was brilliant….Artists have a tendency to work by themselves. You absolutely can do what you love, and I have, but you have to be creative about it.”

-- by Maureen Dixon Harrison

images of Tanya Ragir by Mitchel Evans