Mysteries of life and death, of rituals and deterioration fill the large-scale photographs Lewis Watts has taken on his many journeys to New Orleans. Hands lifting high a coffin are juxtaposed with shy children taking part in their first Mardi Gras celebrations. The work observes quietly, taking in the worn edges of hurricane country where the presence of humans is often marginalized by meteorological poetry and destruction.

Rituals through a Lens

An adjoining suite of new color photos, taken in Cuba, shows the evolving cultural landscape of a vibrant post-Soviet renaissance. Watts' elegaic compositions surround defiantly robust Cubans with magical realist eruptions of color. Gathered into the current exhibition at the Sesnon Gallery, Watts' most recent photographs taken together are loaded with undercurrents of surprise and downhome glamor.

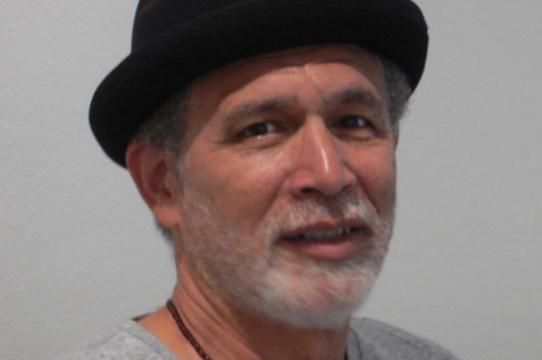

"They combine the old and the new of New Orleans," Watts explains of the exhibition. "Before as well as after Katrina, moments that may or may not come back." Shrines in a voodoo spiritualist center are pictured next to an eloquent trio of hair dryers. Rough,rusted,vibrant, lived ritual comes across in the images, both of the Gulf and of Cuba. "I was part of a UC travel study group that visited Cuba," Watts explains. "I was able to make connections with artists and scholars in Cuba." He found that the aesthetics of Mardi Gras came from Haitians exiled in Cuba. "They then came to New Orleans. It gave them a religious excuse to celebrate," he smiles.

Visualizing the Past

"I've always been interested in visual history," admits the Seattle native. "Most of my family came from the south, and I visited my grandparents every year. Certain patterns started to seem familiar," he says. "So when I became a photographer the first place I wanted to visit was West Oakland. I responded to it immediately. Signs like 'fresh killed poultry.' These were rural people, with improvised storefront churches."

After growing up in Seattle, Watts attended Whittier College and then graduate school in Berkeley, where he taught at UC Berkeley for 15 years before joining the Art Department faculty at UCSC. "When I transferred to Berkeley," he recalls, "I was a political science major. I've always been interested in cultural landscapes." But an art class he took causally, produced what he remembers as an "aha!" moment. One thing led to another, and he "gradually" became a photographer.

"Both my parents were educators, and I might have gone into law, or maybe journalism." The relationship to academia he eventually achieved opened things up for him he admits. "I love teaching for absolutely selfish reasons—I learn from my students."

Watts admits that he "fell in love visually with New Orleans" on a visit in the late 90s, "and then went back regularly until 2008." The photographer was scheduled for a residency in New Orleans the week of Hurricane Katrina. "I went back six weeks later, as soon as they would let us in."

Seeing Large

Watts' current exhibition—which anticipates this year's publication by University of California Press of a book New Orleans Suite, co-authored with Eric Porter—includes work from the past two years of research trips to Cuba. "The book makes you think about the work differently. Eric's written impressions, and my visuals—it's like a conversation rather than an illustrated text," Watts explains. "I'm not through with Cuba yet, by a long shot," he grins. "The more I'm exposed to Cuba, the less I know. It's not my culture—but that's good. It's a challenge." Watts has plans to return to Cuba soon to photograph Carnival. "Carnival isn't easy to photograph, because it's in August and it's hot," he laughs.

Large digital prints currently occupy the photographer's studio time. "I'm interested in how scale might affect my work. And I'm now trying to print on canvas. It's actually an advantage, because you can roll up the work for sending or for storage. " His current large-scale work is shot in film and then digitized. The process helps me see things."

The exhibition currently showing in the Sesnon Gallery should prove enlightening both to the photographer himself, as well as to viewers. "It's exciting to see these artifacts in a formal setting," he admits. "I'm interested in seeing people's responses.